What Even is a Const?

“The qualifier

constcan be applied to the declaration of any variable to specify that its value will not be changed… The result is implementation-defined if an attempt is made to change aconst.”— The C Programming Language, 2nd edition, Section 2.4, pg. 40

So it’s very simple: use const to make a variable have a constant value.

const int CONSTANT = 137;

It’s a small thing, but valuable. Making things const is, in my opinion, one of the easiest and most effective ways of improving most C code, and I will now discuss why.

Become a Better Programmer!

The Principle of Least Privilege is one of the most important rules of writing good, comprehensive, secure software—and yet, it’s also a completely optional rule. The original formulation of the rule is as follows:

“Every program and every privileged user of the system should operate using the least amount of privilege necessary to complete the job.”

The rule extends not just to the system-user level or the program level, but also to the function level. It’s more common to see this rule as useful strictly from a security perspective, but for software development this aspect of the rule makes it even more useful:

“Intellectual Security. When code is limited in the scope of changes it can make to a system, it is easier to test its possible actions and interactions”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principle_of_least_privilege#Details

When I first started digging into massive legacy codebases (aka. being an employed C++ developer), I found that it was impossible to change the code without fear of impacting functionality in other parts of the code. Even at the class level or the function level, making changes to the code bordered on impossible at times. Part of the reason was because many variables were class variables when they could have just been local function variables—that probably merits its own article—but a major cause was that const was used very sparingly within larger functions.

For sake of brevity, see the very heavily abbreviated example below:

void MyClass::functionThatCalculatesSomething(MyData & d, float & a, float & b)

{

int myIntermediateValue;

// 50 lines of code...

myIntermediateValue = d.number + d.someOtherNumber * d.someOtherFactor;

// 25 lines of code...

if (d.someMagicalFlag)

{

myIntermediateValue += FIXED_CONSTANT_OF_SOME_KIND;

}

// 25 lines of code...

a = myIntermediateValue * someOtherValue;

// Function returns somewhere...

}

Most programmers use const when defining global constants or other obvious constant values—something like const int BUFSIZE = 1024;. However, they often neglect using const inside of a function with multiple intermediate values. It rarely matters much for a short function; however, in a massive function you are unfamiliar with, anything that is mutable can be changed in ways you don’t immediately understand without seriously studying the function. A good way of examining how this code works is playing around with it and seeing what can be made const that isn’t already const.

These are the sorts of functions that I’d regularly run into. When making changes to our example function, it becomes difficult to track exactly where myIntermediateValue comes from and what other factors affect its value—especially since it was modified throughout the function. So, when I’d go in and modify this code, I’d first create a version that looks more like this:

void MyClass::functionThatCalculatesSomething(const MyData & d, float & a, float & b)

{

// 100 lines of code...

const int myIntermediateValue = d.someOtherNumber * d.someOtherFactor + d.number

+ (d.someMagicalFlag ? FIXED_CONSTANT_OF_SOME_KIND : 0);

a = myIntermediateValue * someOtherValue;

// Function returns somewhere...

}

Or to avoid the ternary operator (which could have easily caused a hard-to-spot bug if I didn’t put it in parenthesis), I’d do something like this instead:

static int calculateMyIntermediateValue(const MyData & d)

{

int myIntermediateValue = d.someOtherNumber * d.someOtherFactor + d.number;

if (d.someMagicalFlag)

{

myIntermediateValue += FIXED_CONSTANT_OF_SOME_KIND;

}

return myIntermediateValue;

}

void MyClass::functionThatCalculatesSomething(const MyData & d, float & a, float & b)

{

// 100 lines of code...

const int myIntermediateValue = calculateMyIntermediateValue(d);

a = myIntermediateValue * someOtherValue;

// Function returns somewhere...

}

Essentially, entering this large confusing function and making all constants const helps us out in at least 2 key ways:

- It ensures

myIntermediateValueis not modified or adversely affected by any changes we might make to the logic of this function in the future. - It reveals simple ways to break down larger confusing functions into smaller, pure functions that can be changed without worrying about possible side effects the function may have.

What many C/C++ programmers don’t realize is that, beyond just access specifiers like private and public, const allows the programmer to prevent (or allow) write access to any variable for the duration of its scope. Just as it is frowned upon to leave variables public unnecessarily, so too should it be frowned upon to leave variables mutable when they could have been declared as const.

Why Don’t People Use Const?

If const is so good, what keeps people from using it?

About that quote from K&R at the beginning of the article, you’ll find it scribbled towards the bottom of the page and the end of the section, almost as an after thought. And indeed, you’ll rarely see Kernighan & Ritchie use the keyword in their examples. When they do define constants, they tend to use a macro define (or manifest, as I’ve heard some people call it):

// define usage, which ignores the type system

#define MY_SPECIAL_NUMBER 137

They also tend to write old-style C functions that declare all their variables uninitialized at the top of the function like so:

// K&R pg. 59 top of their example main function

main()

{

int c, i, nwhite, nother, ndigit[10];

// ...

}

I think this contributes to their rare usage of const. Even if a value in a function will become constant after a certain point, they’ve already defined their variables at the top of the function. Not to mention that last sentence of their quote from the beginning of the article: in typical C fashion, const’s behavior is implementation-defined. Luckily, pretty much all compilers in the real world will behave correctly, throwing a compiler error when a programmer attempts to assign a value to a const variable—the effect of const is now defined by C++ standards, and I’m sure recent C standards have since done the same.

And really, defining a const variable is sort of an oxymoron:

variable, adjective

Likely to change or vary; subject to variation; changeable.

— The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, 5th Edition

Possibly this verbiage confuses some people?

And let’s not forget the pain of typing an extra keyword, which many people will never do unless required to make their program work.

There is a reasonably valid interpretation of this counter-point, however. A programmer I greatly respect rarely if ever used the const keyword because he composed his code into short, simple functions. Littering the code with const everywhere can make the code appear more visually cluttered, potentially hurting visual clarity. I ultimately agree that a succinct function not exceeding 10-or-so lines is easy enough to follow without using const.

While I respect the sentiment, I stand my ground in saying that const is worth using even in these simpler contexts. Avoiding const in the name of simplicity is more of an argument against C & C++ than an argument against const. Just because it’s more verbose to use const doesn’t means we should forgo its use entirely.

If there’s one thing Rust gets right, it’s definitely this:

// In Rust, variables are const by default

let MY_CONST = 5;

// And must be made explicitly mutable

let mut MY_VARIABLE = 5;

There’s also always the chance that your simple, easy-to-understand function might someday grow to a 50 line behemoth. Doing the right thing and making variables const the first time you write the code will increase clarity and reduce the risk of bugs in the function as the code grows.

If all constants are marked const, it also supplies more information to the reader that anything that is not marked const is a variable that, for one reason or another, gets changed in the body of the function. This knowledge reduces the chance of future modification to the function breaking because the programmer will know what variables to be especially careful with when ordering new lines to a function.

Finally, I guess I’m also obligated to link this Hacker News comment—even if I disagree—which argues that since you can just cast away the const, it can cause very hard-to-spot bugs. While I do agree that const in C and C++ is not perfect because of this possibility, I wouldn’t consider it an argument against using const. Rather, I’d consider it an argument against using const_cast or incorrect C-style casts, while continuing to use const judiciously.

Programming Languages Serve the Programmer

So yes, const is completely optional. However, good code must both accomplish the task at hand as well as communicate its purpose clearly to future programmers. By making things const and removing uninitialized variables, the possible states the program can be in greatly diminishes, making it easier to understand.

On uninitialized variables, this comment from Lobsters gives an excellent example of what I’m getting at:

Widget eitherWay; // ← nobody wants this state! if (planA.has_value()) { eitherWay = Widget(planA.value()); } else { eitherWay = Widget(planB); }C++ initializes eagerly. Nobody likes that.

— https://lobste.rs/s/syxfbv/problems_with_move_semantics_c#c_zcv0qr

That bizarre, uninitialized state that nobody wants is incredibly annoying because it prevents you from making eitherWay a const. For this reason I prefer doing either this:

const Widget eitherWay(planA ? planA.value() : planB);

Or an intermediate function if the logic is too complex for a ternary:

static Widget buildValue(std::optional<Plan> const & planA, Plan const & planB)

{

if (planA.has_value()) {

return Widget(planA.value());

}

return Widget(planB);

}

// ...

const Widget eitherWay = buildValue(planA, planB);

Or since we’re in std::optional we can do this:

const Widget eitherWay(planA.value_or(planB));

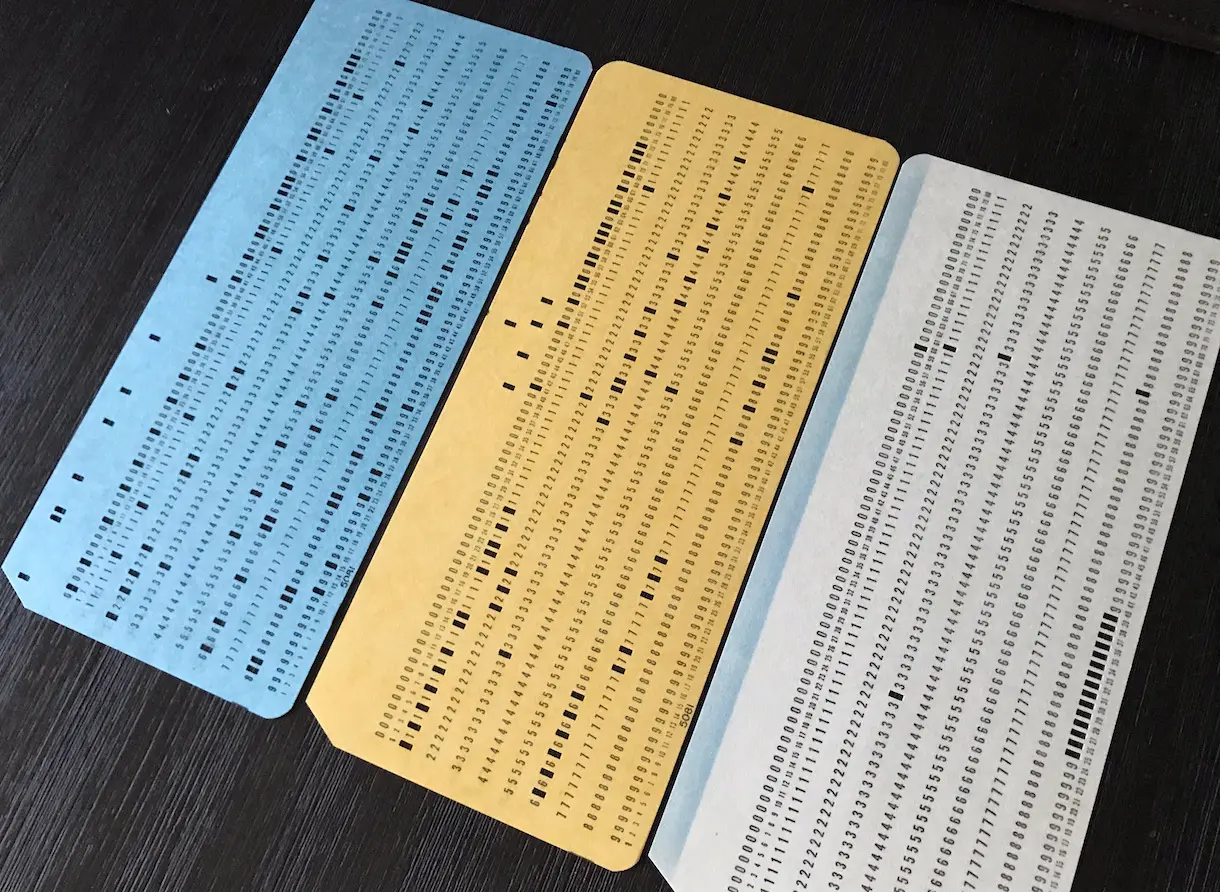

All this stuff might seem “pedantic” or “philosophical” since it doesn’t impact the functionality of the program, but it really does make a difference. Programming languages serve the programmer, not the computer. If we wanted only to serve the computer, we’d still be using punch cards.

By writing more expressive code, intent becomes clearer, bugs become fewer, and code faster (not substantially so, as it’s really not for performance it’s for clarity).

So yeah, use const.